When laughing is no longer funny! The taboo subject we are too embarrassed to talk about...

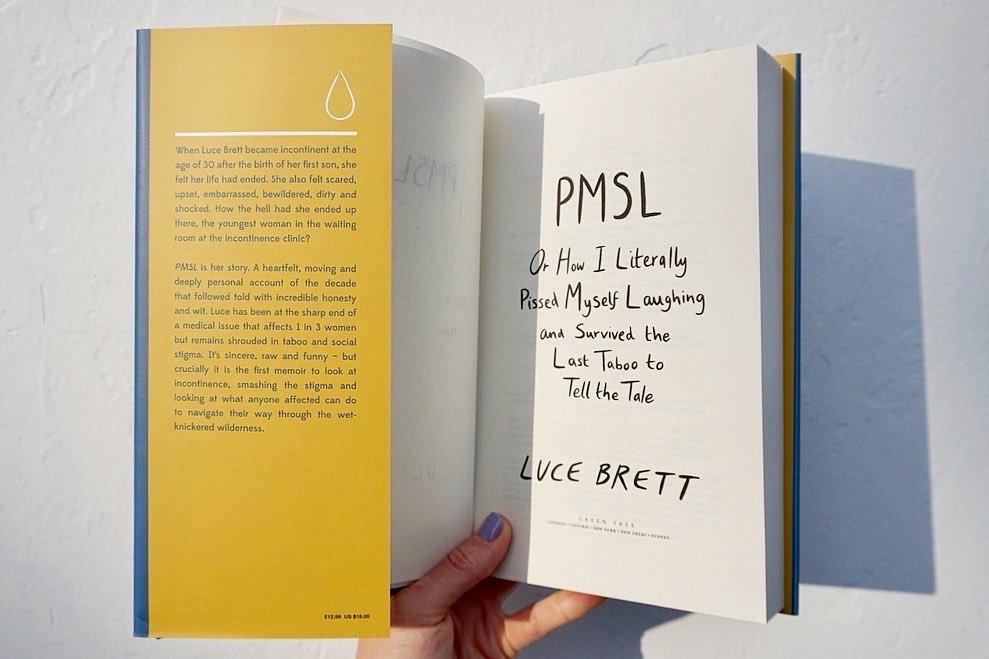

Book sleeve of Lucy Brett’s book

Up to a third of women are affected by urinary and anal incontinence, which can cause physical, psychological, and sexual problems. In a recent episode of BBC Radio 4 Woman’s Hour, they discussed the need for better support and care for the thousands of women whose lives are devastated by incontinence after childbirth. We interviewed Lucy Brett who wrote a book about it.

Tell us about your book and what led you to write it

My first book is an incontinence memoir which people have described as 'uncompromising', 'hilarious', and 'brave'. The subject matter is full-on and it looks both at my story, and how a bad birth had ramifications that lasted over a decade, but also a wider story of how women's bodies have been stigmatised and made taboo and how common health issues like incontinence - which is as common as Hayfever, (let that sink in!) is treated in medical settings and elsewhere, and why women take an average of 7 years to get help.

Its full title is PMSL: Or How I Literally Pissed Myse- which is a bit of a mouthful, but we really felt, as it was a memoir that was partly about busting taboos and challenging the way everyone (medics, governments, employers, women themselves) talk and think about women's bodies, and it was a personal story that probably reflected more people's experiences than we'd like to admit, we should be really clear.

According to a recent Guardian article, one in three women have trouble controlling their bladders or bowels after giving birth. Why do you think we don't talk about this more?

There are loads of reasons - personal, familial, social, political, religious. From jokes which make incontinent people patsies to internalised ideas of disgust. Some are connected to shame, to modesty, and privacy, but also a wider sense that female sexual anatomy is taboo and should not be spoken about. That periods, or incontinence, or hysterectomies, or whatever aren't polite or rank men out completely.

The knock-on effect of this is that when something goes wrong many people feel unable to get help or simply don't have the words.

But with incontinence specifically, there is also the huge swathes of information. For example, in women of a certain age (a category I find myself facing at 45) it is presented in the media as normal - when in fact incontinence is common, but it isn't normal, and it can almost always be cured or at least ameliorated with the appropriate interventions. And those might simply be physiotherapy which is right for you, lifestyle changes (eg: what or how much you eat and drink), use of pessaries or other tools. It is only in fairly rare cases something more invasive eg minor or major surgery is needed.

The situation is worse for much older women, where incontinence is a factor in falls (which impact life expectancy), a complication of many conditions, and something that is sometimes created by care situations where there isn't enough time to help people go to the toilet independently so they are effectively forced into pad wearing.

Many women feel embarrassed and ashamed to talk about their pelvic problems, especially with their partners. What can we do to break this taboo?

It is such a tough one because talking about these things does come at a cost sometimes and I want people to know when they hear about the book, that that is okay. As in, the whole situation is a nightmare and we should try to make the world a place where these conversations are common and people are well educated about their body and sympathetic and kind rather than shaming. BUT the fact is the situation is hard and it is okay if you do find it hard. I get it. I still get ashamed and embarrassed. When I first wet myself in Mothercare when my son was a few weeks old I thought I would never get over it. Years later, at a work party, out out, it was just THE WORST. And leaking/losing control of my body in front of my husband, or during sex, well, that wasn't an easy bit of bravado for me either. It made me quite depressed (studies show anxiety and depression are very common in incontinent people but that is another fact that is rarely talked about). But you know, what writing this book, and talking about the subject a lot has taught me is that a lot of people have these stories, and are desperate for some help, but also most people are capable of being pretty brilliant about it too. We just don't give them the chance to know how because we don't talk. Most of us are capable of understanding bodies are just bodies, you know? Bodies are machines that sometimes break and it is rubbish for that person when it happens. I think it was hard for my husband, sure, but he was amazing about it from the off. Crucially though, in all of these situations - most medics, physios, GPs or nurse practitioners will understand it too. And many of them will be able to help.

It is common to feel alone or isolated, and like you’re the only person with this problem. What can be done to address this?

Lucy Brett

Yes, it really is. And that was one of the main reasons I wrote PMSL - I wanted it to feel like your friend's really clever big sister - someone you know well enough to listen to but not so well it feels intrusive - sitting next to you in a pub, or café, or park, or whatever and telling you about her story and what it all meant to her and how she started to make sense of it and what the tests were really like and how she survived it. Because I had noticed that when I had spoken about my experience before I ever thought about writing about it, there had been magic in that action, and people felt validated to tell their own stories. I can't tell you how many women have said to me 'I've never told anyone this before...' Or 'Only my mum knows'. Some of them are women who've been holding a tricky birth story, an injury, or a continence issue, tightly inside them, often letting it affect their lives, their fashion choices, their relationships, and their working lives, for decades.

I suspect the key is in educating children about all the parts of their bodies from the start and challenging stigmatising behaviour from the off, and all the time. It is a big job though, stigma around incontinence can affect everything from whether men and women have the right bins in their toilets to public policy and charitable donations and funding.

Have you seen any shifts in behaviour?

Yes. I think it is happening. In healthcare policy, and in terms of more high-profile conversations. More than I could have imagined when I first became incontinent at the age of 30. The silence is beginning to break. After my book, several others followed with different and brilliant takes on it too. There is the right information out there.

I've also heard amazing stories from medical professionals and men and women themselves who told me how they got help, encouraged their partner to, or learned about their daughter, father, mother, grandmother, etc's life from the book. I've heard of women taking my book to see a surgeon as a way of starting the conversation to get help. That is thrilling, not because I'm brave, but because hearing a story and feeling validated made those people so brave.

You were invited to Finland in April 2022 to the TISCARE2022 - Technologies and Infrastructures of Sustainable Continence Care to discuss your book. Can you tell us more about this experience?

It was fantastic because it was looking at something that I explore a bit in the book but which is so important - sustainability and how you marry up good continence care and support, with being environmentally friendly and thoughtful. I learned loads, including about causes of incontinence for example birth injury, some cancer operations, MS, dementia, Parkinson's disease, and differences in care in different parts of the world.

It was a huge privilege to speak there as there were so many experts, in primary and secondary care but also global policy, development, patient involvement, continence products and innovation. They asked us to think about what the answers are. I can't design a pad or a pair of washable knickers that combine comfort, not irritating your nethers, and actually being able to catch the sort of amounts of wee that actually come out when you are bladder incontinent, or a decent product for bowel incontinence which would enable someone to confidently work or exercise. But I could stick up for women in the room. And not just women who look like me, women who, for example, might not have access to running water, or a toilet, or for whom birth injuries are reasons to be ostracised by their community.

What advice would you give to any Cinemamas out there who might be struggling with incontinence but are too embarrassed to talk about it?

I would say that there is a lot of information out there. Buy my book or one of the others. Read some articles, maybe consider some physio if your GP can offer it or you can self-refer. And, crucially, try to remember that there is a lot of good quality help and care available and you are not alone. Look at the numbers - in Europe, all the figures convene around about 1/3 for bladder incontinence, and 1/10 for bowel. And those are potentially underreported.

But also, it isn't your fault. You didn't get birth or breast cancer or whatever caused the incontinence, 'wrong'; it isn't something shameful about you. You are not a fool for feeling embarrassed or doing something wrong either. If you haven't worked out quite how you want to cope with it or sort it out yet, that's okay. Go steady. If I can do it, you can. (I'm so sick of incontinent people being somehow blamed for not getting help, that's just as big a pile of bullshit as the rest of the shame and stigma!). Just know that a lot of good helpful stuff is out there, ready, and that going early may make help even easier. And that I'll be cheering you on.

If you want to learn more about Lucy, head to her blog when you ARE that woman